Indigenous Histories of my Homeland

This blog post was written on August 30, 2020. On January 5, 2025, I added a section of news articles to provide updates on the repatriation of Manitou Asinîy.

Have you ever wondered who lived on the land of your hometown before your ancestors? I really started to wonder in earnest this summer. Four generations ago, my family were Norwegian homesteaders that came to the Alberta prairies, some even by covered wagon, from states such as Minnesota and North Dakota .

I thought, “this land was certainly not empty prior to their arrival, so why haven’t I learned any history of my village, county, or region before the settlers?” It’s barely, or not at all, mentioned in our community cookbooks, our local museum, or even in social studies throughout elementary and high school. I recall fur traders and the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Years ago, my buddy Chester, mentioned to me about an ancient, Indigenous ceremonial ground just outside of the village I grew up in. I gathered that he was describing the Viking Ribstones. I didn’t really follow up and truthfully, I wasn’t mature enough to pursue local history at that time.

Turns out, I made incorrect assumption. Surprise, surprise… as I’m sure you have found out (as I have the hard way) that assumptions don’t serve us in the slightest. Chester was right.

Fast forward to 2020, a year that is dedicated to learning and unlearning, questioning previous assumptions, and looking for answers and actions. I asked again, “Who was on the land before my ancestors?”

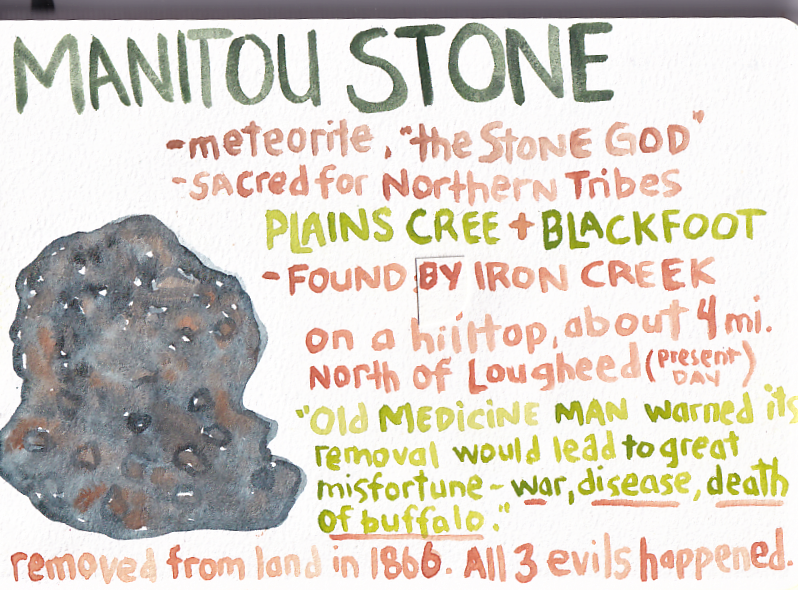

I reached out to an acquaintance from my hometown who pointed me in the direction of the Iron Creek Meteorite and Battle River Valley. It’s also known as the Manitou Stone, or papamihaw asiniy in Plains Cree, and is currently housed in the Royal Alberta Museum. I was also directed to a history book on the Battle River Valley and found out that is the ecological area of my hometown region.

The Manitou Asiniy is a meteorite; 320 lbs of almost pure iron that has been dated to be about 4.5 billion years old. It is a sacred stone to the Indigenous people of what is now Alberta and Saskatchewan, including more tribes than the Plains Cree and Blackfoot listed in my illustration. From a certain angle, it is said that the face of the creator can be seen in the stone. For generations upon generations, the Manitou Asiniy was located on Straw Stack Hill near Iron Creek until 1866. A Reverend named George MacDougall, a Protestant Methodist, removed the stone to relocate it to the Mission at Fort Victoria (about 100 km NE of Fort Edmonton) in hopes drawing more Indigenous people to the Mission if the stone was there. MacDougall was warned by the Indigenous that there would be dire consequences as result of the stones removal and yet it was still flagrantly taken. What this story shows me is a lack of respect and disregard for the wishes of the Indigenous peoples of the Battle River Valley.

I have more research to do about the following 100 years to find out how they were driven off the Battle River Valley. Significant events happened soon after the removal of the Manitou Stone starting with a devastating smallpox outbreak that killed approximately half of the Indigenous population of the area. Then, the death of the buffalo and resulting starvation of the tribes living in the valley. In 1876, after ten years of devastation to the Indigenous people, Treaty 6 was signed and the Battle River Valley was now under the colonial powers and reserves would soon be established.

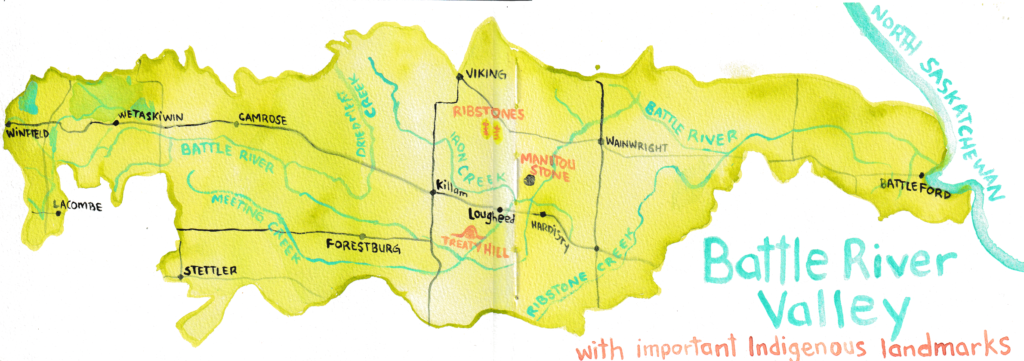

I go deeper into the history and the land. To try and make sense of it all, I ended up drawing a not entirely accurate map of the Battle River Valley and then plotted the important Indigenous landmarks in the area. This includes the Ribstones, Manitou Asiniy, and Treaty Hill. To layer on a modern context, I included some of the primary highways and municipalities of the region.

“Treaty Hill” was a traditional meeting place for Indigenous people who lived in the area. It is a noted location in the Palliser Expedition and as frequent place of assembly for the Surcee tribe (who are now known as the Tsuu T’ina First Nation who reside near Calgary) and are thought to have left the area before the signing of Treaty 7. To add to my surprise, Treaty Hill is Hisliwaornis Kahkohtake in Plains Cree that translates to “flag hanging hill” or “flagstaff hill”. The name of the county I grew up in (and had no idea of the etymology of its name): Flagstaff County.

Many different tribes have lived in the Battle River Valley:

- Blackfoot

- Metis

- Plains Cree

- Surcee

- Stoney

It makes me dizzy contemplating the missed opportunities, the learning, the relationships that have been missed because this history hasn’t been embraced.

The Manitou Asiniy Gallery in the Royal Alberta Museum is currently closed due to COVID-19 precautions. The diorama is supposed to recreate the feeling of the land where the stone used to lie in the Battle River Valley, near the Iron Creek.

There have been discussions about returning the stone to the First Nations. For now, it is held at the Royal Alberta Museum until the tribes decide they would like to house the Manitou Stone elsewhere. It is complicated as Indigenous leaders agree the stone belongs to all First Nations, not just one, which why there has been no resolution of who or where it would be returned to.

What the Iron Creek region lost all those years ago because of the stone’s removal and, more importantly, the Indigenous people, is incalculable. I feel sorrow that this history is not widely known.

In terms of documenting history, how do white people move forward to act on Truth and Reconciliation? In this case, I would love to see us un-centre our homesteader history and focus on other perspectives – not just in cities but in our smaller communities too. I’m not saying ignore the homesteader experience; let’s also give other perspectives the same attention and consider how it’s all connected.

I seriously wonder, is it just me who didn’t know this? It all feels obvious to me now. It was relatively easy to track down information and to learn about it. Did I have my head in the sand, scared of what I would find? The only thing I can do is lean into the discomfort and continue researching.

Are you interested in discovering the Indigenous history in your hometown? I’d love to hear about your experience.

Research Sources

- Canada’s Iron Creek Meteorite by C.E Spratt

- Battle River Watershed Alliance website

- Heritage Barns of Flagstaff website

- Prairie People and Places: Stories from the West website

- Spirit of the Stone by Wayne Arthurson

- First Nations college calls for return of sacred meteorite from Alberta museum by Jen Gerson

- For a look at the Manitou Asiniy Gallery

- Focus on the Gallery: Manitou Asinîy, Royal Alberta Museum from Kubik, Museum Exhibit and Fabrication designers who worked on the new RAM.

- The Battle River Valley by J.G MacGregor (book borrowed from the University of Alberta)

News Articles on the Repatriation of the Manitou Asinîy

- Manitou Asinîy will be returned home, thanks to the efforts of Elders, leaders and funding from Alberta By Crystal St.Pierre, Windspeaker, October 14th, 2022.

- Creator’s Stone meteorite to be returned to original site in Alberta By Sarah Chew, Cole Fortner, and Alejandro Melgar, CityNews Edmonton, September 30, 2022.

- Returning Indigenous artifacts from RAM important but complicated, experts say By Stephanie Swensrude, Taproot Edmonton, March 22, 2024.

My great grandparents, Sam and Susan Kendrick had a homestead south of Lougheed near Bellshill. I have been to the Iron Creek Museum a few times and met Fay Davidson. She told me about Treaty Hill. I really enjoyed your article and want to learn more. Thank you soo much.

Wonderful! One suggestion: Good to date your article. Agreements are underway to create a special indigenous building for the Manitou Stone with Indigenous architect Douglas Cardinal’s designs. Land outside of Edmonton, where buffalo roam!

May 29,2024- Wonderful! One suggestion: Good to date your article. Agreements are underway to create a special indigenous building for the Manitou Stone with Indigenous architect Douglas Cardinal’s designs. Land outside of Edmonton, where buffalo roam!